What is Grant Evaluation? And Why Do It?

Many state and federal agencies announce funding opportunities or grants through formal solicitations for entities that provide or support program initiatives across the spectrum of human social services. Within those solicitations, the agencies also include a section for a formal evaluation or assessment of the initiative. The main purpose of the evaluation is to assess if and how the efforts of the funders, agencies, and/or grantees involved bear results. How effective has it been to fund that particular initiative and what outcomes have been achieved? Evaluations measure what’s working, what’s not, what needs to be improved, and in some cases, what’s the return on investment.

But First… Types of Evaluation

Broadly speaking, there are two main types of program evaluation: internal and external.

External evaluation is carried out by someone who is not directly involved in the development or operation of the initiative being evaluated. An external evaluator has some advantages, including objectivity and the ability to look at issues from a fresh perspective are a few among them. An external evaluator also has a few disadvantages, namely a lack of familiarity with project-related decisions. Such an evaluator may not, for example, fully appreciate why the development team chose to act in a particular way, or appreciate the thinking that lay behind certain decisions. Sometimes, the project team may feel threatened by the external evaluator and feel that alien values or a negative, 'nit-picking' approach are being adopted. However, these issues can be resolved based on mutual understanding and once a relationship has been established between the parties involved.

External evaluation is carried out by someone who is not directly involved in the development or operation of the initiative being evaluated. An external evaluator has some advantages, including objectivity and the ability to look at issues from a fresh perspective are a few among them. An external evaluator also has a few disadvantages, namely a lack of familiarity with project-related decisions. Such an evaluator may not, for example, fully appreciate why the development team chose to act in a particular way, or appreciate the thinking that lay behind certain decisions. Sometimes, the project team may feel threatened by the external evaluator and feel that alien values or a negative, 'nit-picking' approach are being adopted. However, these issues can be resolved based on mutual understanding and once a relationship has been established between the parties involved.

Internal evaluation is carried out by someone from the actual project team. An internal evaluator has the advantage of understanding the thinking behind the development and potential problems that have arisen in the programming. They are also likely to command the trust and cooperation of the other members of the team. On the other hand, such an evaluator may find it difficult to make any criticisms of the work carried out, and, because of their close involvement with the project, may be unable to suggest any innovative solutions to such problems that are identified. An internal evaluator will know only too well how the members of the group have struggled to produce their course, curriculum, or package, and may shrink from the thought of involving them in more work.

However, before an evaluation of an initiative can actually happen, there are steps and processes that must be completed.

How the Grant Evaluation Process Works

The process of grant evaluation begins with responding to a proposal, typically known as a Request for Proposal (RFP). RFPs are often announced by a funding agency which could either be a local, state, or a federal entity. In the education arena, for instance, the funding agencies are typically the U.S. Department of Education, the National Science Foundation (NSF), NASA, the U.S. Department of Labor, state education agencies (SEAs), local school districts, four-year universities and two-year colleges, not-for-profit organizations (NPOs), and philanthropic foundations.

Sometimes, as program evaluators, we engage in the RFP process from the beginning when a prospective grantee (or an eligible applicant) contacts us via our website, or a referral, or by other means to engage us in the proposal writing and reviewing process. The applicants request us to complete the evaluation section of the proposal. Once awarded, we are automatically hired as their third-party evaluators. However, in other cases, there are exclusive grant evaluation RFPs that we compete for via a formal bidding process with other professional evaluators.

The Request for Proposal Bidding War

Once an evaluation RFP is announced on RFP websites maintained by either the funding agencies or third-party paid subscription websites, the “chase” begins. The process includes:

- researching an incumbent, if any

- assessing competition

- attending a pre-bid conference, if planned

- asking questions about the RFP and scope of work

- assessing the organizational capacity to write the proposal and the ability to complete the work once the contract is awarded

- scoping out the project work, timelines, deliverables

- budgeting for the completion of work

Within an organization, after the writing team decides to respond to the proposal, a proposal writing process with deadlines is set in motion. This often involves long and sometimes tedious hours contributing to or writing the full proposal, then making edits, incorporating input from other team members, finalizing the draft, and getting approval from all involved. A proposal typically consists of several sections:

- a letter of interest

- an introduction and understanding of the project

- a general evaluation plan with evaluation questions, research methodology and a logic model, data collection methods, and analytical techniques

- a management plan or organizational capacity

- a timeline of activities and deliverables,

- a budget

Appendices (if required) are added to the document. A full proposal can run anywhere between 15 to 200 pages depending on the funding agency’s specifications and requirements. This multi-step process indicates due diligence on part of the proposer and shows that the potential contractor is thorough in taking the time to research the area of interest, understand the project needs and its stakeholders, shows its ability to meet client expectations, and is ready to take on the work as soon as it is awarded.

And Then We Wait…

Next, the anxious waiting period begins. Typically, the awards are announced within a month but this can vary widely. Funders consider technical and non-technical criteria in making their decisions. Technical criteria are based upon various characteristics of the vendors, including:

- general qualifications and past performance

- understanding of the project

- proposed research design and general approach

- references

- cost

There is often an interview process to allow the funder to clarify any remaining questions. Before making an award, sometimes, the funding agency sends follow-up questions and/or “best and final offer” to the prospective contractor, which may be an indication that the award will be made to the said vendor.

You Win Some, You Lose Some

It can be frustrating to not win a contract you have worked hard on. Sometimes our references are checked and budget negotiations are made—and yet, we are not awarded the contract. Often times, the funder mentions the reason(s) for rejecting a proposal. Some of the most commonly stated reasons are:

- cost/budget

- location, prior experience, and capacity of the vendor in relation to the funder’s needs and expectations,

- weak reference(s)

- lack of clarity in the proposal.

There is no pat on the back or any payment received for all the billable hours spent in researching, planning, and completing the proposal. However, we pick ourselves up and the cycle begins when another RFP of interest is announced.

The Professionals --- Really, Who Are Grant Evaluators?

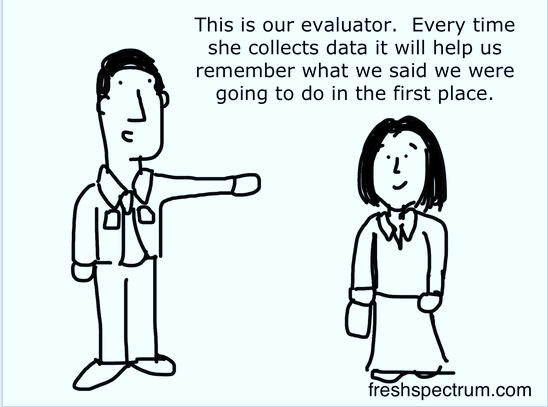

As grant evaluators we tend to wear several hats. As an educator, I have found myself teaching clients about the value of evaluation in general and specifically with the initiative on hand: What do we as evaluators uniquely bring to the table? How can we be better partners and collaborators in the success of the initiative? At the same time, we are assuring them that we are not evaluating them but their program. Ultimately, the time spent building trust with a client is vital for demonstrating the value of evaluation both in the short and long terms with open communication as a critical mechanism for an overall success.

Some Evaluation Challenges Ensue

More often than not, evaluation budgets are small. They are either a percentage of the whole project’s budget or just an arbitrary amount set aside by the program staff. Unfortunately, some agencies do not set aside a fixed budget percentage, which leaves the field wide open to sometimes very contested and lengthy negotiations and even fierce competition. There are also cases when the clients underestimate the scope of work or don’t factor in labor and staffing matters of the evaluator(s). In several cases, as evaluators, we end up “eating” the costs of the evaluation or in rare cases simply have to walk away after the contract award due to failed negotiations.

Some clients expect evaluators to do large-scale, complex, and rigorous evaluations with limited funding. A few of them may even expect us to “find” positive results. Some clients even seem to know the results before we have even started the evaluation work! All the above reasons can be equally challenging especially for a small consulting business with low overheads, modest revenues, and a lean staff. Working on “soft monies,” drumming up business almost every year as the projects end can be a time sink. Federal program evaluations tend to be large-scale and long term (3 to 5 years) however, a vast majority of others are short-term (under 6 months to a year).

Gaining a client’s respect for evaluators and evaluation as a whole is an exercise in itself. Working with and not on the client is important so they gain confidence in us and our work.

Why Did I Become An Evaluator?

For the Money and Thrill?

Not really!

Scratching the Entrepreneurial Itch

I consider myself a reasonably practical person when it comes to money. Having a paycheck that comes in regularly and knowing where I’m going everyday has given me a sense of security. I started working when I was 22 years old. The job and the paycheck not only taught me the value of money but also about financial security and planning.

Not having a regular paycheck was something that I didn’t necessarily want to give up when I opened my education consulting business, MN Associates, Inc. – about 13 years ago. The same year, I started graduate school full-time. I neither had a full-time job nor a regular paycheck.

“Becoming” A Program Evaluator: A Calling?

In mid-2002, I was just out of a master’s program in Applied Sociology from George Mason University. I had joined one of the education consulting firms based in Arlington, Virginia as a research assistant. Working in a small, closed-knit education evaluation firm had its advantages. The company had under 10 full-time education researchers/program evaluators. People were personable and willing to take me under their wings. A team of up to three staff members routinely engaged in a wide variety of PreK-16 contracts that spanned: STEM education, teacher quality and preparation, early childhood education and family literacy, after school programs, and education technology among others.

As a junior staff member, I was exposed early to almost all the above mentioned areas in the two years that I spent there. I facilitated meetings and conferences, traveled across the country to collect data on study participants via personal interviews and focus groups, crunched statistical data, analyzed results, and wrote or co-wrote technical reports. It was my then boss and mentor who introduced me to the consulting world, more specifically, the grant evaluation world. I found my calling: Program evaluation.

What I have learned from the two-year experience was invaluable and greatly helped me set the stage for opening my shop later in 2004. The place and people also made me actualize completing a Ph.D. in Research Design and Methodology. I think the degree and training have been useful to engage me as an education researcher/evaluator, write proposals, stay competitive, and grow my business.

A Big Leap of Faith

Working full-time and attending grad school was challenging. I left the firm in late 2004 to start my Ph.D. program at George Mason University in the College of Education and Human Development department where I specialized in Research Design and Methodology. While in grad school, I kept working on smaller education research and evaluation projects with several individual consultants and organizations alike that were willing to give me work on a short-term basis. The “side” income enabled me to supplement my several research assistantships on campus. Upon encouragement from our Certified Professional Accountant (CPA), in December 2004, I opened a consulting company, which didn’t take off until 2008, the same year when I graduated with a Ph.D.

Defining “Success” and Being Flexible

During my 15-year tenure in the consulting business, I have either contributed or completed around 250 proposals with a success rate of about 30%-40%. On average, we respond to about 30 proposals per year. A majority of our business is based on current and past client referrals and returning clients (over 60%), followed by competitive bidding process (~20%), and partnerships with other vendors (~10%).

Being always flexible, understanding the client’s needs and meeting their overall expectations are keys to success. Sometimes the funder modifies the scope of work or asks the contractor to reduce the cost upon award of the contract. Taking the time to meet and talk with the funder to understand the scope of work is critical before starting a project. Other intangible aspects of grant evaluation success are developing a strong professional relationship with the client and respecting their limitations. Being objective and having the ability to report on contextual findings are critical to good evaluation.

Substance AND Style: The Final Evaluation Reports and Who Is Really Reading It?

Writing a good evaluation report that tells a story is truly an art. A report that is carefully crafted and that has both substance and style is something that every evaluator should strive for. In our work, we provide interim reports every year in addition to shorter data summaries that provide formative assessment of the program and in the final grant year, a summative evaluation of the whole initiative that tells the whole story. Having a feedback loop is essential to the overall health of the grant as well as for building trust with the client.

assessment of the program and in the final grant year, a summative evaluation of the whole initiative that tells the whole story. Having a feedback loop is essential to the overall health of the grant as well as for building trust with the client.

Along the way, we have learned how to better gauge our audience. We have learned to know:

- who is going to read the reports

- how they are going to use them

- whether our reports appealing to the larger public

- whether our findings are usable

- if the evaluation ultimately helps the client improve, scale up, sustain, and/or help them to look for additional findings

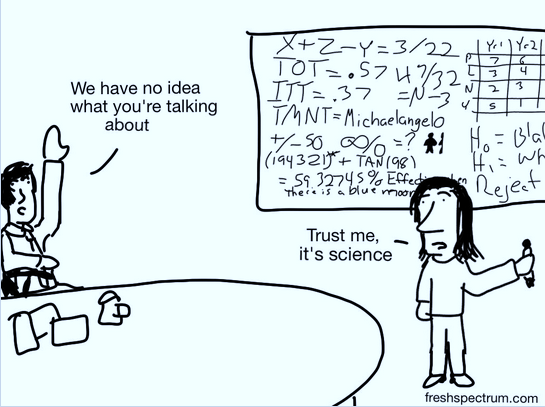

The Client is Always Right

Taking clients’ comments to heart and making necessary changes as appropriate without compromising the integrity of the evaluation is something we have learned by experience. Just by saying, “Those results are true, just trust us! Use them as they are!” doesn’t always work. By way of an example, one of our school district clients wanted an evaluation report with statistics. However, we learned later that the project team had limited understanding of statistics. After we sent our draft report for their review and comments, it was discouraging. Their comments made it clear that the presentation of results needed to be altered significantly. Data needed to be supported by graphs and charts with fewer statistical tables. The final product ended up being far more visually appealing and reader friendly, and we told them a story! Telling a story makes reporting relatable, memorable, and the data more palatable. Last but not least, spending time and money to engage a professional editor and also a graphic designer to put the finishing touches are important, too.

Evaluation Consulting 101 Tips: How to Get Started

Sometimes, I receive emails and even phone calls from recent graduates and young professionals who are considering a career in grant evaluation or want to open their own consulting business. They often ask, “How can we get into the business of grant evaluation?” “How does it work?” “How did you open your own business?” “How do I grow?” I tell them my personal story and give them a few tips. When starting out, there are a few other ways of gaining experience and a foothold in a certain area that one may not be too familiar. One of them that I have personally found equally rewarding is partnering with another consulting firm or a consultant as a sub-contractor. However, it should be done with great caution. Communication is key. Getting clarity on the scope of work, division of labor, and consulting fees (all in a written MOU) are critical for a successful and fruitful relationship. Other useful tips include: marketing one’s skills, having really good time management, communication, and writing skills, the patience and perseverance to follow-up with prospective clients and collaborators, and to not give up easily.

What’s Next?

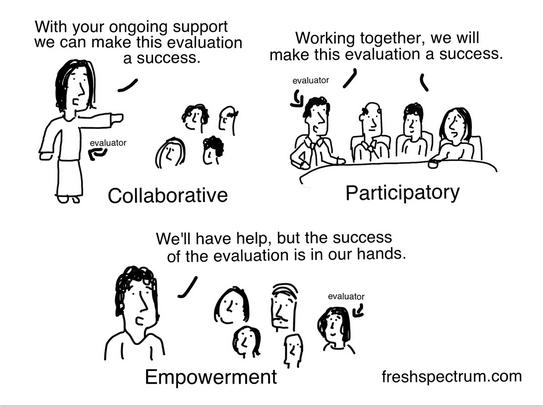

It’s been over 13 years since I first opened MNA. It’s been a long and an interesting journey. Now, we are a team of five, including four program evaluators with diverse educational and work experience and an administrative staff person. Our general approach in conducting a grant evaluation is to be theory-based, cross-functional, action-oriented, participatory, collaborative, and cooperative. We aim to be rigorous and produce reports that are succinct, contextualized, and accurate.

It’s been over 13 years since I first opened MNA. It’s been a long and an interesting journey. Now, we are a team of five, including four program evaluators with diverse educational and work experience and an administrative staff person. Our general approach in conducting a grant evaluation is to be theory-based, cross-functional, action-oriented, participatory, collaborative, and cooperative. We aim to be rigorous and produce reports that are succinct, contextualized, and accurate.

We will likely continue working in the grant evaluation arena for as long as there are grants of interest and more importantly, we have the will, enthusiasm, and drive to chase, research, write, work, and repeat the process!

All along this journey, we have learned one big lesson: Grant evaluation is not for the faint-hearted!

References:

A special note of thanks to Evaluator Chris Lysy (freshspectrum.com) for giving permission to use a few of his cartoons.

Reviewed and edited by Nina de las Alas and David Keyes, team members at MN Associates, Inc.

See http://www2.rgu.ac.uk/celt/pgcerttlt/evaluating/eval4.htm for differences between internal and external evaluation.

About Kavita Mittapalli

Kavita is the CEO and Founder of MN Associates, Inc. (www.mnassociatesinc.com), a PreK-16 consulting firm based in the metropolitan DC area. MNA provides research and evaluation services to clients across the country. MNA’s work are funded by grants from the National Science Foundation, U.S. Department of Education, Labor, Transportation, private foundations, not-for-profit organizations, and school districts and state education agencies. Kavita has a B.S. in Agricultural Sciences (India), a master’s in Applied Sociology and a Ph.D. in education research design and methodology from George Mason University. She can be reached at kmittapalli@mnassociatesinc.com

Kavita is the CEO and Founder of MN Associates, Inc. (www.mnassociatesinc.com), a PreK-16 consulting firm based in the metropolitan DC area. MNA provides research and evaluation services to clients across the country. MNA’s work are funded by grants from the National Science Foundation, U.S. Department of Education, Labor, Transportation, private foundations, not-for-profit organizations, and school districts and state education agencies. Kavita has a B.S. in Agricultural Sciences (India), a master’s in Applied Sociology and a Ph.D. in education research design and methodology from George Mason University. She can be reached at kmittapalli@mnassociatesinc.com

To learn more about American University’s online Graduate Certificate in Project Monitoring and Evaluation program or online MS in Measurement in Evaluation program, request more information or call us toll free at 855-725-7614.